In depth

Conde Corbal was born in Pontevedra, in 1923, in a nationalist atmosphere that was supported by Castelao as the leader of a group of painters who, thanks to the President of the Provincial Council, Daniel de la Sota, transformed this city in the origin of the so-called Galician historic avant-garde with names such as Maside, Torres, Souto, Colmeiro and Laxeiro.

Painting will become the most important part of our art in the coming decades thanks to the work done by those awarded with a grant of the Deputación. This art can be classified as a renovation in the context of a very strict socio-political structure, which was still defending the regionalist components of the Galician painting.

He started his studies at a private school in Michelena Street and later on, he went to another one in Mendez Núñez Square. He used to spend his summer holidays in two different places: the beach in Placeres and Pazo de Ramirás, on the way to Ourense. Two differente landscapes and two diffferent atmospheres: the first one, the conventional summer holidays; the second one was the landscape of the Galician small villages, getting in touch with the farm work, the traditional stories and the genuine Galician spirit.

He started working at Bibiano Osorio Tafall´s laboratory in Michelena Street and this makes him get in touch with biology. He began his studies at high school where he realized that he was fond of plastica arts; during the boring lessons, he used to copy the drawings of the German artist Hans Liska, that were published in the Adler magazine. “In a context of dominated people, it was Liska the one who gave us a bit of Europe whith his essentially graphic drawings”, Conde Corbal said to Antón Castro in a private conversation.

Approaching his painting means to understand the artist’s compromise with the reality around him. He creates a world of silence where the words that try to get an explanation out of certain social function get drowned. He tries to take the art to all the social strata as a means of expression assumed by the people in Galicia.

This painter is the heir to the long tradition that made art a document of the world or a reflection of reality. The marginal reality of the Galician people finds in Conde Corbal’s work a unity at the service of a new aesthetics that is genuinely Galician and that wants to show the real face of our people.

He estarted studying Law and Chemistry at univesity, but his pictorial vocation made him leave his studies. After working in differente jobs, managing a ceramics factory in Benavente or Working in a wolfram mine, he settled in Ourense in order to increase his artistic activity. He started using watercolor ang gouache in an analysis of the traditional Galicia through its people and landscape, which will be the main characters in his work.

His first exhibition takes place in 1958 and it is favourably received. This is an event that will mark his link to the painting as compromise and aesthetic manifesto. It is at this time when he started one of his most important activities: his collaboration in magazines and newspapers. He starts in La Región, illustrating a section called “Ourense Perdurable”, together with Vicente Risco. This contact with Risco will be very important in his point of view about culture and art.

“From the beginning, I wanted to communicate, I worked to say…-but without taking into account the bourgeois standards of communication”; this is his the point of view about an important part of his work: art as communication. His didactic willingness and the research of new ways of expression are going to be basic features to approach his work, which will inxlude a complex variety of thematic and linguistic registers. Therefore, we must analyse Conde Corbal’s aesthetics according to its diversity and reichness, taking into account three different but complementary chapters: his journalistic work, his engravings and printings and his pictorial work.

The journalistic work

His contribution in different newspapers has to do with the graphic part. He begins this work in La Región, illustrating the series “Villages and Cities of Galicia” [1961-1962]. When Risco dies in 1963, he leaves the newspaper from Ourense and starts working in the one from the city where he was born, Diario de Pontevedra, where he illustrated with his drawings different reports on etnography, festivals, proccesions and folklore from Galicia, as well as different series about the North of Portugal and the Pontevedra River, a geographical and cultural area to which he was always very related. This daily contribution includes interesting series as the one entitled “Stone Crosses, Breast-plates of Souls”. He moves from Pontevedra to Vigo, where, besides his pictorial activity, he collaborates with Faro de Vigo. Together with González Martín he makes “The Miño Way” and he illustrates with his drawings controversial topics such as the one of the reservoir in Castrelo de Miño. Later on, he collaborates with La Noche, with a series of drawings: “Costa da Morte”.

In 1969 he goes to Madrid, where he develops a diverse work in the field of art. He collaborates in the Chan magazine with suggestive illustrations following Valle Inclán’s style an with a kind or esperpento when configuring the line of the drawing. He travels to Brittany and later on he settles up in Vigo temporarily. At this time he starts his intensive dedication to printing, which will contiue until his death. His contributions to the Galician newspapers [La Región, La Voz de Galicia, Faro de Vigo] will be come more sporadic.

The printing

The engraving or printing is the most interesting part of Conde Corbal’s work, the one with which he identifies himself, due to its communicative connotations. If the aim of the engraving is the mass reproduction of the work so that it will get to more people -making the artistic product cheaper-, it is necessary to use more logical procedures, which are not so expensive or complicated. This was Conde Corbal’s search. He gets a new technical procedure whith a very distinctive and peculiar way: he draws on a transparent sheet of plastic, which is not used in the conventional plate, with pasted pigments. Later on, he gets its transformation thanks to the protogravure, in order to get, with great fidelity, the plastic values and the qualities that the artist wants to get.

For more than 20 years, Conde Corbal only tries to get visual communication in his engravings-printings. Acccording to the artist, this visual communication has to be lively and active for an observer who can come from any social stratum. In short, he tries to look for and highlight different levels of information in order to create a discussion in the social conscience of any individual. Taking this concept or art-communication as the starting point, Conde Corbal reinforces the sense of the message in the recipient, who gets it emotionally and also through the clarity of the content. For the author, it is basic to encourage the people’s conscience with the artistic image as an element that creates interest in anything and as a way to educate sensitivity. Ernst Fischer’s words in La necesidad del arte are quite appropriate in this case: “The main task in a socialist society where the art market is not stocked up with the mass production of the capitalist speculators, is a double one: on the one hand, to make the observers find pleasure in art, to arise and stimulate comprenheicnsion, and on the other hand, to highlight the social responsibility of the artist”. We assume that, neither the artistic compromise nor the denunciation involved in the message, are excluded. In this sense, Conde Corbal connects with the line of the social realism or social expressionism, as it was called by the critic and historian Valeriano Bozal, attitudes that were pre-sent in people such as Grosz or Renato Guttuso, painters admired by our artist.

Since 1960, Conde Corbal carried out more than a thousand printings, grouped together in different thematic series with an aim close to the popular pedagogy. We could say that the topic, literary or narrative element, is restricted to monographic situactions that come from the deep Galicia, except on rare occasions: the sea or the countryside in Galicia, its monuments, its people, its cities, the sea world and the fishing equipment, the rural area, the literature and ist men, the anthropology, the ethnography, the fauna, the flora, the rivers, the coastline, the historical experiences, the war… it is Galicia as a whole from an artistic point or view, grasped with an accurate pantheistic love, with the identification of somebody who knows and gets engaged with the people an the land. Conde Corbal’s art is an art for the people and it can represent, even when there is lack of understanding, those concerns of the harshest social testimony, heir to Castelao in the Album nós. Herein, some of his most important series:

– There are three series related to literature and more precisely, in Valle-Inclán’s work, 1969-1970: “Luces de bohemia”, “El amor y la muerte en Valle-Inclán” and “La etnografía gallega en Valle-Inclán”.

– Related to ethnography: “Cruceros, petos y santos” [1966], with a prologue and comments by A. Garcia Alén, “Pontevedra: la tierra y su gente” [1967], with a prologue by Filgueira Valverde.

– Dealing with the cities and their surroundings, the provinces an their monuments: “Ribadavia” [1974], “El Vigo viejo”, “El Ourense perdurable” [1960] with captions by V. Risco, “Ourense monumental” [1964] with captions by Ferro Couselo, “Pontevedra monumental” [1965], “Pazos de Pontevedra” [1972].

– Related to the Galician sea world, its life, its people, its fishing crafts, the sea fauna…: “La dorna y los que viven de ella” [1977], “Gentes del mar de Vigo”, “La dorna y sus trabajos”, “Peces, moluscos y crustáceos”.

– Dealing with the Galician fauna and flora: “Peces del río”, “Pájaros”, “Árboles y arbustos”, “Florecillas silvestres”, “Mamíferos”, “Insectos”.

– Related to trips and itineraries: “Costa da Morte”, containing mora than eighty printings. As an excepcion, we have some series that have nothing to do with Galicia: “Un viaje por Italia” and dozens of monographs about Brittany and the Baixo Miño.

– Documentary and historical series: “La Guerra Civil en Galicia”, containing more than a hundred printings.

In Conde Corbal’s work the aesthetic option of the printing will be an expressive and graphic one, coming from a realism that has been distorted in a conscious way, very expressionist, distorting, as in the goyesque esperpento and with a strong stroke in the gestures. Carol Maier, an American literary critic and specialist in his work, says that the best way to understand the graphic reason of Conde Corbal’s engravings is by means of the relation they have with Valle-Inclán aesthetic principles. He has an aesthetic aim reminding us of the stonemasons, the tympanums and breastplates or souls, Valle-Inclán’s words, calling fakes to the ustraists, reviving Goya and taking the heroes to the Carreixo do Gato in the XII scene of “Luces de Bohemia”, assuming the role of Max Estrella. And that sincerity appears in the personal testimony of many of his exhibitions in a kind of narration of the people that he depicts for posterity: “I would like to mention them one by one as in a catalogue…-They are sea people, sailors, fishmongers, crybabies, weeping people, orphans and widows, work at night in the fish market…-they are pious women, devout women, offered to walk on their knees, the religious processions in Amil and O Corpiño, farm workers from inland, people who work with the hoe, hard workers…-”. These words by the artist were used to introduce many of his catalogues and they made the observer get ready to get into the social dynamic linked to the crative work that the artist suggested.

In his language we can find expressive and constructive. The first one, in his ability to show the emotional aspects of his figures by means of the distortion, even when the represented thing is a simple object or an architectural monument. He places the characters and the scenes in their context but he also makes the distorting dynamics special, according to the agitated rhythm of a new look. Thus, the vision of an urban landscape, let us think about “Ourense perdurable”, can be approached in many differente ways by the observer and his perception may depend on his state of mind. Otero Pedrayo used to say that for Conde, “the admirable agreement and concordance between people and houses was discovered, as well as the one between the different times and seasons or the landscape of a black alley or a little square.

From the constructive, he assumes, apart from the analytical aesthetics of the lines that define rhythms and organic structures, the capacity of the educational message, that personal transforming aspiration of the society that gets the image. This social aim is similar to the one developed in Germany by the New Objectivity in the 20s, which had reinforced a concept that was more graphic than pictorial, or the one by the aforementioned Grosz, one of the masters of the satiric-social drawing. It is also similar, in some engravings, to the aspiration of the aesthetics of the Mexican muralist.

However, it is in the italian Guttuso where Conde Corbal finds the best parallelism. The Galician artist coincides with him in a testimonial way, not only in the aesthetics but also in the content. Guttuso defines his realism coming from its relation to society. In a lecture, “Sulla via del Realismo”, he said that a work of art has to be understood by everybody, at least partly: “through this part that is clear for everybody, it will be possible for those who are more instructed, more sensitive, more cultivated…-to approach the work…The other part that has to be clear for everybody is the theme…”. Other components in his aesthetic labour, when talking about printing, are the ones studied by the aforementioned critic, Carol Maier, from five different perspectives:

– The cultural background in all his works, due to his great passion for reading, provides his work with a very solid base of reliability and didactics. He was always surrounded buy books or notes. Conde Corbal was an eager reader, not only of words but also a reader of life, his environment and everything that was around him and had an influence on him. As regards the reading material, it cannot be denied the influence of Valle-Inclán’s work and he even said that Valle-Inclán was the one “who was going to lead his hand”.

– His attempt to take the Galician people from the obscurity to which they had condemned themselves, arises a kind of collective memory about their identity reflected on the series about the people, the places, the traditions…-shaping a culture o which sometimes we are not aware. The link to names such as Risco, Otero Pedrayo, García Alén or Ferro Couselo supports the ethnographic value of many of his works. Thanks to his work many immortalized places from Galicia, and many others that do not exist nowadays, are still alive in our memory.

– The distorting, as the third proposal in Conde Corbal’s work, is a mixture of memory and feeling, getting an expressiveness by means of the line and arousing in the observer a feeling of concern and unease. He follows a way that goes far away from the reality established by a society whith a realistic pattern of behaviour that is fully accepted, which the painter usually destroys from his consciousness-raising point of view. And, many times, he gets to situations where the worrying, the masquerade, the grotesque part of life prevail over such a conventional reality.

– The humanizing nature, offered in his engravings, can be trailed throughout his work, as well as the other components. When he corrects the dehumanization reflected in the previous point by using the technology of the engraving, this means of expression becomes his favourite, “the most expressive and the fastest way to communicate to people what I feel for my land”. A relation with the machine that makes our humanization possible thanks to that collaboration from which both parts profit.

– The last situation has to do with a word that belongs to the world of the engraving: “firmness”. This immobility that he can get on the plate, the immobility of the scene, offers him the opposite effect: the possibility of continuing with its spreading, trying to get to the highest number of people. This is an aim that defines his way of action and that will prevail in his work. He looks for a detail that can be observed by the highest number of people in any place or situation.

This is the main aim in Conde Corbal’s aesthetics: his engravings are an answer to the vibrant reality of his world lacerated by his graphic concepcion of the line.

The pictorial work

In his pictorial work, Conde Corbal takes to the canvas or to the board, his most usual material, the same topics as in the engraved work. It is defined by a similar aesthetics, in this case with varied and multiple pigments, especially gouache, watercolor and acrylic. The acrylic is his best means of expression, the one with which he defines his personality in the world of the Galician painting.

Heir to the granite aesthetics, within the Galician historical avant-garde in the first part of the 20th century, primitivist and espressionist, the artist was able to interpret with freedom and lack of inhibition the most gestualized, spontaneous and figurative part of the Galician neo-espressionism. This attitude was an avant-garde in the new European spirit of the German and Italian people in the eighties – neoexpressionists and transvanguardists. Before being taking by the post-modernism as the aesthetics imposed to define the return to the painting, Conde Corbal took to his paintings concepts such as iconic and stylistic eclecticism, the feeling of tradition, the autobiographic reflection, narration and expression, a recreational and free reference to the colour, a free figuration… – But, together with the pleasure of painting and the stylistic freedom, there is the iconographic reason, the tribute to the content, the consciousness-raising image that has to get to the people, because, for him, art always has a function: to educate in an emotional way and by means of an operative aesthetics based on the expressionist deformation. We have different examples, such as Mending the Nets [1971], The trail [1984], The Octopus at the Port [1983], Canned Fish Factory [1976], O Berbés [1981].

The same topics, identical communicative aspirations are present in his paintings, which are brightened with the warmness of the brilliant acrylic, with the presence of the red or the yellow colour, with the aggresiveness of the orange colour or the harmonious reason that involves the use of the blue colour. The distortion that suggest cries and restlessness, the total movement of the figures and the lines in the horizon are the main characters in his compositions, the product of an attitude towards life that has transformed the expressionist inheritance of the old ancestors, from the popular stonemasons to those who carved the Romanesque tympanus or the Baroque altarpieces. Anyway, Conde Corbal suggest a testimonial portrait of Galicia from a plastic freedom without limits. Curiously and as we have mentioned before, his painting led to a horizon where traditions were recovered, something that the post-modernism had looked for at the beginning of the eighties due to the crisis of the previous models, with an amazing strength and originality. He was able to translate the identity into the chromatic sign, the anthropology into a topic of popular aesthetics and the autobiographic presumptuousness into intense gestures to link the destiny of art to life by means of the subjects and the way of dealing with them. A testimony of sincerity that goes together with the expressive invention that assumes the concepts and patterns of the classic Mexican muralist and that is shown as simple expressionism respecting the line of the drawing with thick strokes, but that also reinforces the granitic character –a sign of identity generated in the Galician historical avant– garde-which he gets with the light and the plasticity of the shading. But the artist insists on the link between the cons-tructive and expressive structures, with a certain geometrical reason with which he visually arranges the perception of the images that arouse the emotions that they transmit to us.

The painter enjoys the mixture of different ranges of colours with a clear aggressiveness, as if it were an avant-garde manifesto, but exemplified directly on the painting. The use of orange, red or yellow in their strongest chromatic range, emphasizes the expressionist element. Conde Corbal’s work is only a little bit colder when he uses a colour that is a must in our Galician culture: blue in all its varieties. The application of the colour to some expressive patterns, on the basic of the distortion from the drawing, causes the silent dynamism of the image through winding lines, in which the mobility of the figures is highlighted: this effect increases the feeling of a agitation that the author is always looking for in order to create atmospheres full of vitality. This vitality is understood as an element of the painter’s rebelliousness, as a way to face society and to interpret it as a moral obligation. We can find here the presence of the creator who wants to fill the painting with the testimony of his life, with the documentary base of somebody who perceives Galicia as a feeling and he does it by means of the aggressive and devastating paintbrush and also by agitating the shapes, by taking care of the compositions, that usually represent a particular horror vacui of clear Baroque tradition.

Sometimes he uses a formality that comes from the world of the Galician popular arts, from the breastplates of souls to the altarpieces of different times, that were so traditional in our artistic world, models that deny the emptiness as an element that shapes the space in the painting.

The distortion of the figures increases the visual impact of the aims in his engravings or printings: from there it comes a feverish and electrifying atmosphere, a place of confusion, as if a creative storm would arrive and would make the observer look for shelter. All this makes his work an updated continuation of the Galician historical avant-garde that had began with Maside, Souto, Colmeiro or Laxeiro in the first years of the century and that was far away from the reionalist clichés of those artists who would only see Galicia as a subjet of the typical folklore.

There are two elements in his work that have to be mentioned. One of them is the use of the nude and the portrait as elements of communication or linguistic elements within the painting. The nude denotes in his work a clear eroticising tendency that leads the painting to other fields without leaving the confrontation spirit. Conde Corbal dignifies, above all, the human figure and the nude appears as if its own strength would fill the canvas: from here it comes a monumentality that is quite rare in the history of our painting. Some works as Nude People on the Beach [1980] or the “Erotic Series”, 1988, are good examples of this.

The other distinctive element in his painting is the use of the portrait. He is a magnificent portrait artist of people close to him, people who are well-known in the community, and also anonymous figures that the observer does not know, unknown people that, in the painting, get the same vital dignity as the ones that we recognize. Once again, the artist highlights the value of the painting as a social element in the field of the popular culture and the people that he portrays always belong to the same typology: sea people, farm workers, young boys and young girls…they are an example of the main characters in different sceneries and contexts in a real or an invented ethnography, through which Conde Corbal gets into the feelings, wishes and hopes of the characters and he is able to undress the soul and to create an accurate X-ray of the Galician maritime-rural reality.

We are not going to make a list of all the exhibitions in which Conde Corbal took part, because we would fill pages and more pages with dates and places; but, it is important to highlight his participation in many individual and collective exhibitions in Galicia, Madrid and United States. Many of his exhibitions follow a new concept, quite frequent nowadays, that of the movement of the works to villages and schools in Galicia, with a didactic and instructive aim. His engravings and his painting were even presented as the illustrative part in conferences, lectures and advertising posters and they were also required by the institutions to include them in their promotional campaigns. We can find his works in private and institutional collections, in public buildings and in museums all over Galicia [Museo de Castrelos de Vigo, Museo Provincial de Pontevedra, Centro Galego de Arte Contemporánea in Santiago…] and also in different Spanish cities, in France and the United States.

Carlos Casares’ comment in the prologue of one of his catalogues is the most accurate to sum up the critical and aesthetic dimension of Conde Corbal’s prolific work, ones of the best visual projects of the Galician art in the second half of the 20th century, if we want to enter the real spirit of the culture and the soul fo this country: “There are not silent people: there are drowned words. If people run out of words, you can be sure that they also run out of freedom”.

ANTÓN CASTRO

X. Antón Castro (1953)

Graduated in Philosophy and Letters and in French Literature, holds a doctorate in Art History. Member of the International Association of Art Critics of Paris, he was a teacher of Contemporary Art and taught master’s degrees and courses at different universities.

He has collaborated in several magazines of art,thought or literature; curated more than sixty exhibitions around the world; he wrote about twenty books about art and current artists. In recent years he was director of the Cervantes Institute in Milan and the Cultural Heritage Institute of Spain.

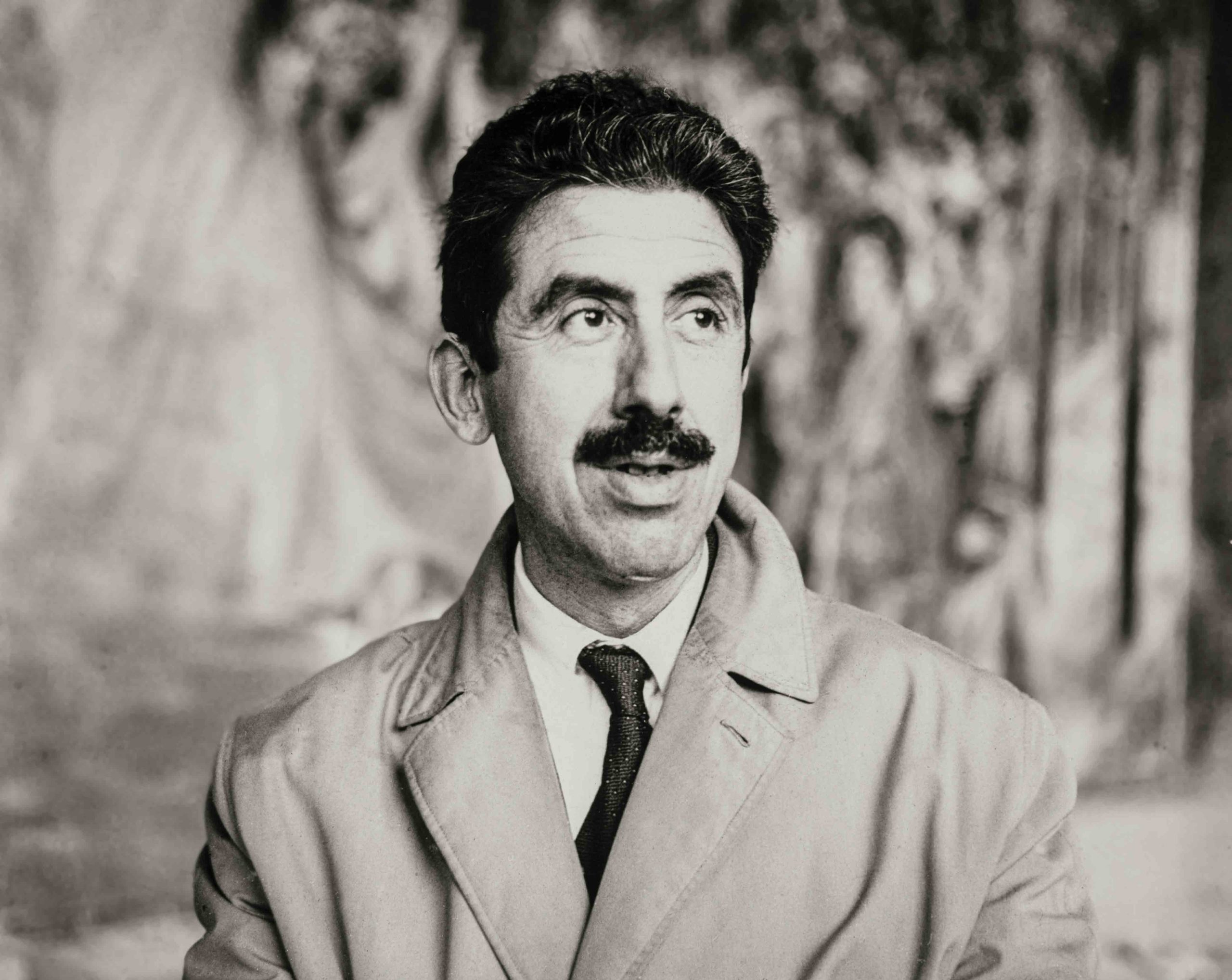

Xosé Conde Corbal, 1959